In 2022, the Communications team partnered with the Web Standards team at Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) to create a video that would explain the importance of web accessibility and how public servants must make sure online information and services can be used by disabled people.

Our hope in creating this video was to spark dialogue across the public service, and to encourage everyone to find out more about web accessibility and improve the accessibility of their work creating and sharing information with others.

The plan

We decided to interview 2 accessibility subject matter experts (SMEs) from the disabled community to learn from their professional experiences working in accessibility with government organisations as well as from their perspectives of living with disability.

Our SMEs were:

- Callum McMenamin, former Principal Advisor for Accessibility, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) — who has low vision

- Daniel Harborne, NZSL Information and Resources Team Leader, Deaf Aotearoa, and Director, Signability NZ — who is Deaf.

At the same time, the Communications team saw this as an opportunity to learn what it means to make and deliver an accessible video — in other words, use a process for producing accessible videos that bakes in accessibility right from the start.

How the plan changed

Initially, the plan was to create 1 video which would explain what web accessibility is, as well as offer some practical tips on how government employees could make their work more accessible.

However, the process of trying to fit all the content into a single, short video opened our eyes to just how naive we were to think we could sum it all up in only 3 minutes. We quickly learnt that web accessibility is a big topic.

We wanted to acknowledge that there is already a wealth of ‘what is web accessibility?’ information available online, and our contribution would therefore focus on why web accessibility is important from a user perspective. Additionally, we felt that the strength of our video was in the strength of its subjects — so to pile on a load of additional information would only serve to dilute the impact.

The project became about making 1 main video and supporting it with 3 further videos that address related topics.

What is web accessibility about?

Fundamentally, accessibility is about designing things so that they don’t discriminate against disabled people. So, accessibility is about human rights.

When we deliver online information and services that are accessible, we help disabled people to live more independent lives and to participate in society on an equal basis with others. So, accessibility is about inclusion.

When everyone is enabled to participate, we all benefit from all the different practices and perspectives that people bring. So, accessibility is also about diversity.

As a Comms professional, my understanding of web accessibility was hazy. Through this process I learnt that, simply put, making web content accessible is about making sure that websites work for disabled people.

Why is web accessibility important?

If information is relevant to me — I’m a New Zealand citizen, I’m living here — I should be able to expect at a bare minimum that there would be captions to videos.

Video transcript

Soft music plays in the background.

At the top of a black screen is the logo for Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa New Zealand Government. Underneath the logo is the text ‘Why is web accessibility important?’.

Cut to Callum McMenamin. On-screen text reads ‘Callum McMenamin, Principal Advisor Accessibility, Hīkina Whakatutuki, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’.

Callum McMenamin: “I spend a lot of time on the internet, you know, in my job and in my personal life, and I encounter a wide range of how accessible those systems are. There are some systems that I basically can’t use at all.”

Cut to Daniel Harborne. On-screen text reads ‘Daniel Harborne, NZSL Information and Resources Team Leader, Deaf Aotearoa’.

[Daniel Harborne uses New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL). Here, he communicates through an NZSL interpreter who translates between NZSL and English.]

Daniel Harborne (in NZSL): “If information is relevant to me — I’m a New Zealand citizen, I’m living here — I should be able to expect at bare minimum that there would be captions to videos.”

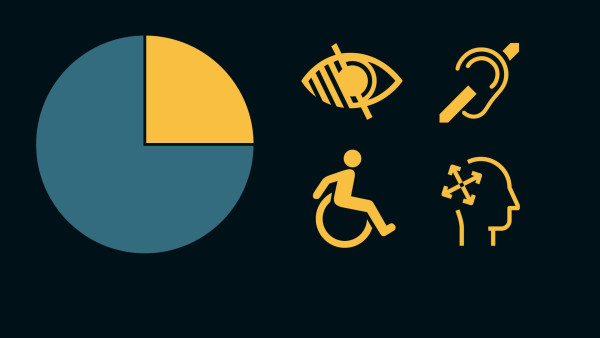

Cut to a black screen. On the left half of the screen is a blue circle. One quarter of the circle changes colour to yellow. To the right, symbols for visual, hearing, mobility and learning impairments are displayed in sequence.

Narrator: Almost a quarter of New Zealanders self-identify as disabled. They have one or more long term visual, hearing, mobility or learning impairments.

Cut to Paul James. On-screen text reads ‘Paul James, Government Chief Digital Officer, Chief Executive, Digital Public Service, Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs’.

Paul James: “New Zealanders with disabilities are our whānau, they’re our kaimahi and they’re our customers. So we provide, as New Zealand government, information and services to New Zealanders and they have an entitlement to that information and services as well.”

Cut to Ann-Marie Cavanagh. On-screen text reads ‘Ann-Marie Cavanagh, Deputy Chief Executive, Digital Public Service, Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs’.

Ann-Marie Cavanagh: “We know that over half of New Zealanders over 65 are disabled, so it’s critical that we make sure that our content that’s delivered through our online channels is easily accessible and that we’re not excluding those communities or those parts of the New Zealand community.”

Cut to footage of a blind person using a computer with a refreshable braille display.

Narrator: “Disabled people often use special hardware and software called assistive technologies that help them access and interact with web content. Sometimes disabled people need content to be in a certain format, such as captions on a video or sign language translation.”

Cut to Daniel Harborne (in NZSL): “And I thought with the COVID situation, when they brought the interpreters on and they were talking about, tonight we’re going to be locking down the country, you know, things are going to be closing. I remember thinking, okay, I need to go and get some food. I quickly dashed out, went to the supermarket, made sure I had enough food. If I hadn’t had an interpreter on screen at that time and I had to read it in the newspaper the next day, or watch the 6 o’clock news the next day to finally have access to know that everything shut, I would have then gone to the supermarket and the shelves would have been empty by then.”

Cut to footage of a web browser navigating from a page on the NZ Government Web Standards, to a page on the Web Accessibility Standard, to the W3C’s page on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1.

Narrator: “The New Zealand Government Web Accessibility Standard requires that public service departments make their websites accessible. This means that each web page needs to meet the internationally recognised Web Content Accessibility Guidelines from the W3C.”

Cut to Ann-Marie Cavanagh: “So it would be important, I think, for agencies to ensure that as you’re building out your digital service delivery and your online service delivery to really start from the get-go to include those New Zealanders with disabilities in that co-creation process.”

Cut to Paul James: “It’s really important that leaders and everyone involved in this work takes a sense of responsibility and obligation to make sure that we do hit those standards of accessibility so that all New Zealanders, including those with disabilities, can access the information and services.”

Cut to Callum McMenamin: “I don’t think everything’s ever going to be perfect. I think it’s always going to take constant effort to make things accessible in the same way it takes constant effort to make information secure and to respect privacy regulations. It takes constant effort, constant expertise. I don’t think there’s going to be a lack of work any time soon.”

Cut to a black screen. At the bottom is the logo for Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs. Above the logo is the text ‘learn more at digital.govt.nz’.

Fade to black.

NZSL version

Our responsibility as public servants

As public servants, our responsibility to make all web content accessible has far-reaching importance.

In the video ‘Why is web accessibility important?’ the importance of and need to prioritise web accessibility — not as a nice to have but as a necessary part of the way we work — is endorsed by Paul James, Government Chief Digital Officer and Chief Executive of Te Tari Taiwhenua, and by Ann-Marie Cavanagh, Digital Public Service Branch Deputy Chief Executive at Te Tari Taiwhenua. It was great to hear this commitment from these senior leaders about our shared obligation to deliver accessible government information and services.

Video launch

On 6 October 2022, the video was launched at the Summit for a Digital Public Service 2022 and introduced to government organisations in a presentation by NZ Government Web Standards Consultant Jason Kiss.

Supporting videos

How can government organisations raise accessibility levels?

It would be important, I think, for agencies to ensure that, as you’re building out your digital service delivery […], to really start from the get-go to include those New Zealanders with disabilities in that co-creation process. This is to really make sure that we’re designing services with them as opposed to for them.

Video transcript

At the top of a black screen is the logo for Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa New Zealand Government. Underneath the logo is the text ‘How can government organisations raise accessibility levels?’.

Cut to Callum McMenamin. On-screen text reads ‘Callum McMenamin, Principal Advisor Accessibility, Hīkina Whakatutuki, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.’

Callum McMenamin: “So one thing that we’re seeing in government right now is some agencies are hiring accessibility experts and I think it can really help push the agenda of accessibility within public sector organisations to have, like, a principal advisor for accessibility, which is my role. And then that allows me to sort of champion that within the organisation. Some of it is creating that kind of cultural shift almost to increase the visibility of accessibility and to get people to really care about it.

“So one other example is MSD [the Ministry of Social Development], for instance, is creating an entire accessibility team. They’re going to be hiring up to 12 people, I think, just to focus on the accessibility of MSD’s systems. So that could be one strategy for the public service to really improve accessible outcomes. It allows more people to specialise in the field and improve their knowledge, and I think that is extremely important for helping everybody because then you’ve got, you know, a central contact person or even a team who can answer all of your questions, who can provide leadership and strategy for how to improve the accessibility of things.”

Cut to a black screen. At the bottom is the logo for Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs. Above the logo is the text ‘learn more at digital.govt.nz’.

Fade to black.

Hire accessibility experts

A common theme expressed in the interviews was the need for hiring accessibility specialists and establishing accessibility teams that include people with lived experience to:

- provide guidance and advice to government organisations

- raise overall capability

- cultivate a more accessibility-aware culture.

Accessibility experts such as Jason and Callum are able to provide guidance on programmes of work within their organisations, as well as lead regular consultation sessions to share their knowledge with kaimahi.

Web accessibility and PDF documents

Video transcript

At the top of a black screen is the logo for Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa New Zealand Government. Underneath the logo is the text ‘Web accessibility and PDF documents’.

Cut to Callum McMenamin. On-screen text reads ‘Callum McMenamin, Principal Advisor Accessibility, Hīkina Whakatutuki, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.’

Callum McMenamin: “What I see a lot of is the public service pumps out a hell of a lot of PDF files. And this isn’t unique to New Zealand either. It’s a problem that governments all around the world have tackled with.

“Some people claim that you can make an accessible PDF, but I dispute that. So the majority of people access the web on their phones and their mobile devices. Often PDFs are designed to be the size of an A4 sheet of paper or even A3. So when that’s shrunk down to the size of a phone screen, it becomes this impossible-to-read little file and you’ve got to zoom in and pan around in order to read it. It’s just an awful experience and I sort of think when we publish PDFs, we’re completely ignoring what people do when they access government content — that they use their phones for the majority of those interactions. So it’s very important to focus on how people are actually accessing content.

“The other thing is, if you’re using an iPhone or Android device, and if you’re blind or low vision or have a reading disability and you use screen reader software, screen reader software doesn’t work very well with PDF files at all. The only instance where they kind of work okay is on Windows with Adobe Acrobat installed. Any other situation and you’re out of luck. So you’d sort of have to ignore reality in order to think that PDF files are a good way of communicating.

“I know that the World Bank, for instance, has done some research on who actually downloads and reads PDFs on a website. They found that around a third of their published PDFs were downloaded zero times. So there’s a lot of data out there and evidence that suggests when people see a PDF file to download, they just don’t do it. So if you publish in PDF only, you’re most likely communicating to no one.”

Cut to a black screen. At the bottom is the logo for Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs. Above the logo is the text ‘learn more at digital.govt.nz’.

Fade to black.

Use accessible document formats

The creation of government web content should always consider the widest possible audience and must include disabled people — in New Zealand, 24% of the population identify as disabled. However, many observations were made in the interviews about how the standard processes and content formats used in government are not accessible to everyone. This reveals a need for creating better guidance as well as more education to build cultural awareness within government organisations.

It’s clear that government employees do not make their work inaccessible deliberately, but perhaps more through habit and lack of knowledge. As accessibility awareness increases within government, hopefully the work coming from our organisations will reflect this.

Why PDFs are a problem

As a prime example of my own lack of accessibility knowledge, I was surprised to learn that PDFs — a document format beloved by government organisations — are not entirely accessible to screen reader users because PDFs are not accessibility supported.

Understand that NZSL is a language, not a literal translation

It’s important to remember sign language is its own language. It’s very different from English. So that means a lot of Deaf people, they’re not fluent in English.

Video transcript

At the top of a black screen is the logo for Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa New Zealand Government. Underneath the logo is the text ‘Sign language is a language, not a literal translation’.

Cut to Daniel Harborne. On-screen text reads ‘Daniel Harborne, NZSL Information and Resources Team Leader, Deaf Aotearoa’.

Daniel Harborne: “It’s important to remember that sign language is its own language. It’s very different from English. So when someone’s using sign language, they’re not following an English word order. They’re not signing to an English grammatical structure. Sign language has its own grammatical structure. It has its own ways of using language. And so, for example, what might be said in a sentence in English can be just said in a few signs in sign language and what might be said in 5 words in English might be needing to be expanded in sign language, because they’re concepts that you’re working from, rather than following a certain grammatical structure. So they are very different languages.

“So that means for a lot of Deaf people that they’re not fluent in English. Their literacy wouldn’t be the same. They wouldn’t have the same literacy ability in English as they would have in use of sign language. So there’s some people whose language level might be a lot younger than their physical age. But I think, you know, being able to have accessibility in both English and sign language is important.

“But then you’re talking about another language again, which is kind of like, you know, the language that people within the government might use because there’s complicated ideas that are being used. There’s quite a lot of jargon, there’s quite a lot of specific terms that are really relevant for government. And I’ve noticed some of those words when I’m reading them, I go, I’ve seen that word before, but I’m not sure the meaning of that when they’re using it within, you know, within that intention, within that sentence.

“So I’m really having to think about that when I’m providing accessibility for the Deaf community in sign language. I want to make sure, you know, I’ve done the research, I want to make sure that I’ve got the right definition of that word and the intention they’re using it as, within their use, so it’s put into sign language as well, equally.”

Cut to a black screen. At the bottom is the logo for Te Tari Taiwhenua Department of Internal Affairs. Above the logo is the text ‘learn more at digital.govt.nz’.

Fade to black.

I learnt that New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) is a wholly visual and gestural language, with its own syntax and grammar that is different to English. This helped me to understand why providing NZSL translations of video output (in addition to captions) is important. It illustrates how nuanced accessibility can be — Deaf New Zealand citizens who communicate via sign language may have a far lower English literacy level than New Zealand citizens who communicate in English. It also reinforces the importance of using plain language in all government communications to make the information as accessible as possible.

What we learnt about making web content accessible

As a Comms team, we learnt a lot from listening to the SMEs talk about the barriers they’ve encountered and what’s needed to make web content accessible.

We started to understand that:

- disabilities are nuanced and varied, as are accessible technologies

- context is critical to all design decisions

- there is no one answer or approach that will neatly address all accessibility needs.

In addition to the many insights captured in the video interviews, here are some simple actions we are now taking to make our mahi more accessible:

- Always add captions to any video you publish — Adobe Premiere and YouTube have auto caption capabilities that are very helpful but must be checked carefully to avoid inaccuracies, particularly with any te reo content.

- Always add alternative text when publishing meaningful images online.

- Always use Styles or markup to rank headings logically when structuring any document.

- Use plain language whenever possible and avoid jargon.

Importantly, we started to lean on the resources available to learn more about accessibility. A listing of some of these resources is at the end of this blog post.

What we learnt about making accessible videos

Interviewing in NZSL

For Daniel’s interview, we contracted an accredited NZSL interpreter.

Initially, we thought that the interviewer would be communicating directly with the interpreter, who was to voice Daniel’s signed responses. However, Daniel taught us how to place the interpreter behind the interviewer, essentially ‘off screen’, ensuring that the interviewer would maintain eye contact with Daniel the whole time, never breaking the line of communication or human connection with him.

Budget accordingly

We needed to source several types of accessibility services for this project, including:

- an NZSL interpreter for Daniel’s interview

- a NZSL Picture in Picture (PiP) NZSL service from Deaf Aotearoa for the ‘Why is web accessibility important?’ video.

These services were important to factor into our budget.

Plan ahead

We learnt that it’s important to get in touch early with accessibility providers so that you know how long it will take to get any alternate versions of your content made.

Our original timeline slightly underestimated how long it takes to commission a NZSL interpretation of a video. However, because it was important to us that everyone, including Deaf people, get access to the video at the same time, this meant we delayed our publication date to enable both versions of the video to be simultaneously published on Digital.govt.nz.

Less is more

Initially, we’d envisioned weaving a series of graphic illustrations into the video and our designer, Wibke Kreft, created several iterations of these designs. Eventually, however, she settled on a single graphic contribution to the project that depicts the significant proportion of the New Zealand population who identify as disabled and the 4 types of impairments that are particularly affected by inaccessible websites: visual, hearing, mobility and learning.

In design, Wibke advocates a ‘less is more’ policy. She also advised on reducing the visual clutter in the opening and closing slides in the videos.

I have my university professor’s voice in my head: “Braucht’s des?” (“Do we need that?”) — with the unsaid, loud question of ‘WHY?’

Similarly, we initially attempted to explain too much in the first video through a voiceover. We decided in the end to focus instead on the power of the insights that came out of the interviews to highlight why accessibility is important.

This approach served to amplify the voices of our SMEs and their lived experiences of disabilities.

The project team

Communications

The Communications team comprised Senior Content Advisor Max Olijnyk, Senior Communications Advisor Lily della Porta, and Senior Designer Wibke Kreft. Communications advisors Freya Sturm and Besa Chembo, and Senior Communications Advisor Joel Hansby also helped in the filming of the interviews.

Web Standards

Web Standards Consultant Jason Kiss provided valuable subject matter guidance throughout the process.

Content Designer Tamsin Ewing provided feedback on the draft themes and key messages for the video in the early stages of the project while she was on secondment in the Web Standards team.

Related resources

If you would like to learn more about web accessibility, the following resources complement the content in the above videos.

About web accessibility:

- What is web accessibility? — Fundamental concepts in web accessibility — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- Accessibility, Usability and Inclusion — W3C

- Assistive technologies — How disabled people use the web — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- Accessibility supported technologies — Fundamental concepts in web accessibility — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- Alternate formats — How disabled people use the web — NZ Government

Web accessibility requirements and guidance:

- The New Zealand Web Accessibility Standard 1.1

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 — W3C

- Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- Web Standards clinics

Making videos accessible:

- Videos — Web content types — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- Captions — Make a video accessible — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

- NZSL video — Types of alternate formats — Web Accessibility Guidance project — NZ Government

About making other types of content accessible that are mentioned in this blog post: