Results of DIA’s accessibility questionnaire last month show practitioners’ keen interest in and enthusiasm for the new guidance that government is developing on making web content accessible.

About the Web Accessibility Guidance Update project

Based on the Web Standards Self-assessments of 2011, 2014 and 2017, government websites continue to struggle to meet the Web Accessibility Standard, which is based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 .

Many government practitioners and vendors consistently display low awareness of what’s required to make digital information and services accessible to all. A survey conducted in 2019 shows that many practitioners have difficulty understanding WCAG requirements as well as basic accessibility practices, and that they’re calling for support.

The new guidance, which will be organised around roles rather than requirements, aims to make it quicker and easier for practitioners to see how to meet the success criteria in WCAG so that websites are accessible to disabled people.

About the questionnaire

The questionnaire put out by the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) was aimed at digital practitioners who specifically design, build and publish content on web pages.

The purpose of the questionnaire was to test the core findings of our research on what we need to do to improve web accessibility guidance for practitioners in New Zealand.

Responses to the questionnaire were collected for 2 weeks in September 2020.

Results

Number of responses

We received a total of 189 responses from digital practitioners working in a wide range of organisations across the public and private sectors.

Testing the roles

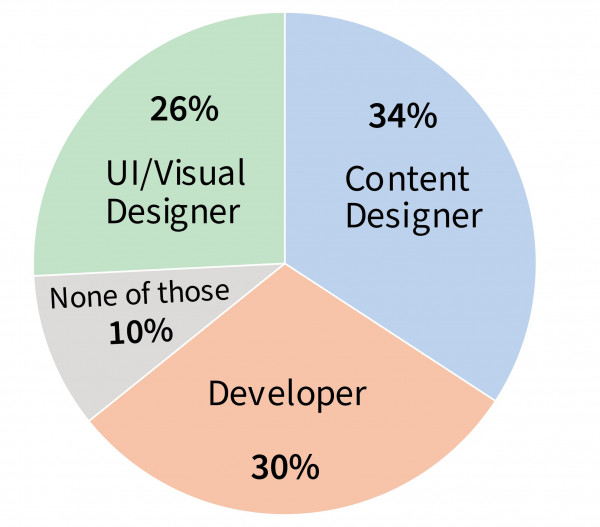

Despite holding over 100 different job titles, most of the 189 respondents identified as having the core specialist skillsets of either a content designer, a developer or a user interface (UI)/visual designer.

Figure 1. Core web accessibility skillsets

Did we get the core roles right?

- 34% of respondents identified as doing work similar to the role of a content designer.

- 30% of respondents identified as doing work similar to the role of a developer.

- 26% of respondents identified as doing work similar to the role of a UI/visual designer.

- 10% of respondents did not identify with any of the 3 core roles.

Respondents who said that they put content on web pages, but that their work was never done by roles like content designers, developers or UI/visual designers, mostly held advisor, analyst, coordinator or senior leadership job titles.

Respondents with user experience (UX) job titles said their work aligned with the skillsets of either a content designer or a UI/visual designer.

Testing the knowledge

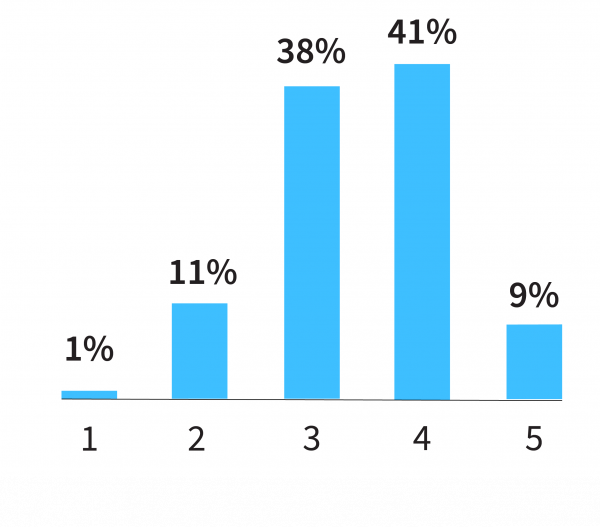

Overall, there was a stark contrast between how highly people rated themselves as having accessibility knowledge and skill, and how negatively they chose to describe their experience of using the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

Figure 2. Accessibility knowledge and skill levels

On a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest level, respondents rated themselves as follows:

- 41% of respondents rated themselves at a Level 4

- 38% of respondents rated themselves at a Level 3

- 11% of respondents rated themselves at a Level 2

- 9% of respondents rated themselves at a Level 5

- 1% of respondents rated themselves at a Level 1.

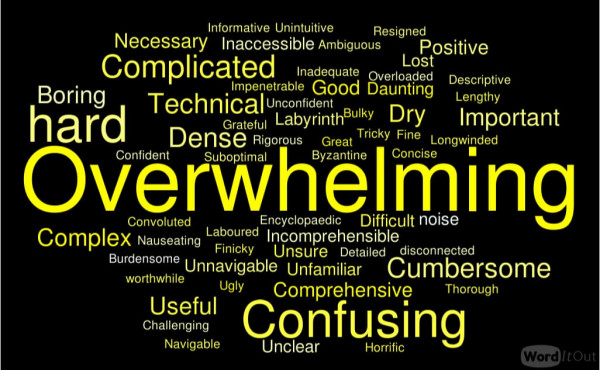

Figure 3. Word cloud of WCAG experience

Word cloud showing the terms respondents used most frequently to describe their experience of using the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) – the bigger the word the more times people said it

See a larger version of the image (PNG 90KB)

Terms appearing in this word cloud

Terms respondents used to describe their experience of WCAG were, in descending order of frequency: overwhelming, confusing, hard, complicated, cumbersome, dense, technical, boring, complex, dry, important, useful, comprehensive, good, necessary, positive, daunting, difficult, inaccessible, incomprehensible, labyrinth, lost, noise, unclear, unfamiliar, unnavigable, unsure, ambiguous, bulky, burdensome, byzantine, challenging, concise, confident, convoluted, descriptive, detailed, disconnected, encyclopaedic, fine, finicky, grateful, great, horrific, impenetrable, inadequate, informative, laboured, lengthy, longwinded, nauseating, navigable, overloaded, resigned, rigorous, suboptimal, thorough, tricky, ugly, unconfident, unintuitive, worthwhile.

It’s surprising that so many practitioners who called WCAG primarily overwhelming, confusing and hard, also rated their accessibility knowledge and skill as high. If the standard defining web accessibility is so hard to understand, how can so many have such advanced knowledge and skill? This certainly does not align with the current state of accessibility of NZ government websites, which remains poor, and this is a possible area for further investigation.

Negative words

The words respondents repeatedly used to describe their experience of WCAG were largely negative. In the order of popularity, the most common words were: overwhelming, hard, confusing, complicated, cumbersome, dense, technical, complex, boring, daunting, difficult, dry, incomprehensible, labyrinth, unnavigable.

Positive words

Positive words were also used repeatedly, but much less frequently. In order of popularity, the most common words were: important, useful, comprehensive, necessary, positive, good, informative, thorough, and worthwhile.

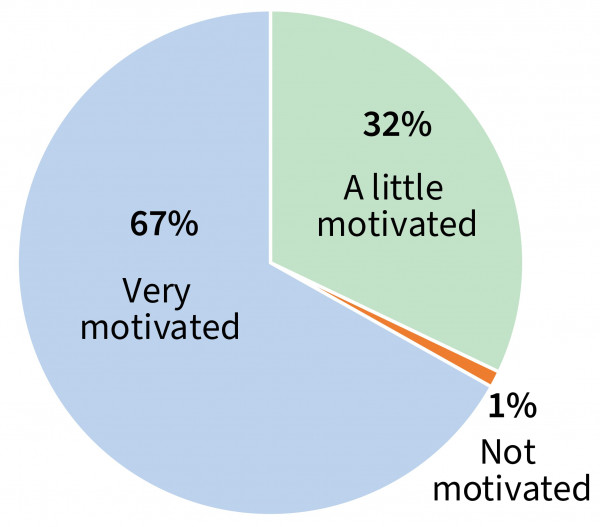

Testing the motivation to improve accessibility skills

Despite how difficult respondents said they find understanding WCAG, the large majority are very motivated to improve their accessibility skills.

Figure 4. Motivation to improve accessibility skills

- 67% of respondents feel very motivated to improve

- 32% feel a little motivated to improve

- 1% feel not motivated to improve.

Reasons for motivation

The common themes in why practitioners feel motivated to improve their accessibility skills were related to:

- having a social conscience

- having experience and an understanding of the impact that inaccessible websites have on disabled people

- having a desire to learn

- receiving support to upskill from their organisation

- knowing it makes sense to design for accessibility because this improves the design for everyone

- knowing it was a critical part of their job

- believing that it should be a government priority.

Reasons for lack of motivation

Reasons why practitioners do not feel motivated to improve their accessibility skills were related to:

- finding accessibility work difficult

- finding WCAG hard to understand

- having little time or energy to learn about accessibility

- believing it costs more to make content accessible

- feeling that their organisation does not care about or prioritise accessibility.

Testing the accessibility guidance topics

While the questionnaire results confirm that the direction of the proposed guidance is right for practitioners, it also identified some gaps in the topics and gave us an indication of which topics are most important to practitioners.

Gaps in the knowledge areas

In addition to the critical knowledge areas listed in the questionnaire, respondents said they also want guidance on the following areas that are particularly relevant to their accessibility work:

- accessible authoring tools and content management systems

- inclusive/Universal design versus accessibility

- JavaScript frameworks and accessibility

- progressive enhancement

- testing with disabled people

- testing with a screen reader

- third party tools and user-generated content (UGC)

- UX research for accessibility

- Voice assistants and accessibility

- Windows high contrast mode.

Gaps in the web content types

In addition to the web content types listed in the questionnaire, practitioners said that they also want guidance on the following types of content that they design, develop or insert in web pages:

- animations – accessibility considerations for incidental decorative animations versus meaningful animations

- cards/tiles

- EPUB3

- toggletips.

A view of which topics should be prioritised

The frequency with which knowledge areas and web content types were selected by respondents will help us to prioritise the order in which we develop and deliver the guidance. Popular topics for each of the 3 core practitioner roles will be the highest priority, especially if there is no guidance available yet for the topic in New Zealand.

Testing practitioner interest in the new guidance

Respondents submitted only positive comments about this project. Many said that this work was necessary and important to them and that they are excited to see the new guidance.

This work is exciting! Our team tries hard to decipher and use WCAG but we would really benefit from simpler, clearer guidance that’s written as a set of plain language instructions rather than a set of success criteria.

People also said that they really liked the questionnaire because it highlighted all the work that they do, along with the specialist knowledge areas that are required to make web content accessible. For some, the questionnaire acted as a checklist and helped identify areas that they did not know that they did not know about.

Questionnaire takeaways

The questionnaire responses received have helped to:

- validate that the problem we are solving for practitioners is the right one

- confirm that the proposed direction for the new guidance is the right one

- identify gaps in the topics people need guidance on

- prioritise the order of the content we’ll deliver based on its relevance to practitioners

- give us confidence to move from the discovery phase into the delivery phase to develop a product people need and will use to improve the accessibility of New Zealand websites.

Where this guidance will be published

The guidance will be published in phases, starting in late 2020, on Digital.govt.nz.

Read more about the Web Accessibility Guidance Update project

Check out our first blog post about this project to:

- see the questionnaire that respondents filled out

- understand the background to this work

- read about the design process we’re using to develop this user-centred content.

New web content accessibility guidance to be defined by practitioner needs.

Published